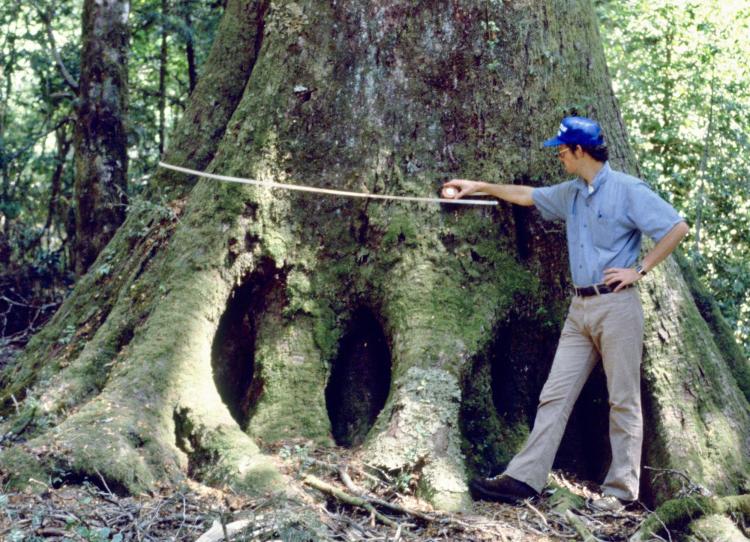

Tom (center) in New Zealand, 1979

I recently interviewed Tom Veblen to discuss being given the University’s highest faculty honor, Distinguished Professor, and learn more about Tom’s exceptional career. I came away with a strong appreciation for his life's work in forest ecology and environmental science. Our Fall 2017 newsletter features a condensed version of this interview.

What does being named Distinguished Professor mean to you?

I’m pleased to be recognized by my colleagues and peers. It’s a real honor to be included in a group of people with such impressive accomplishments as previous and current members of the Distinguished Professor group. It's really an honor to be in the same group as some of the geographers who previously have had this honor: Gilbert White, going way back, and then Roger Barry sometime in the 1990s. In terms of practical benefits, there are perhaps none and that’s fine at this stage in my career. But, I look at it as another piece of evidence for the excellence of our department and also for the importance of the kind of research I do in environmental science and climate impacts on forest ecosystems. So, this honor is visibility for my field and for our department which I think is important.

New Zealand, 1979

My case is very similar to a lot of people who get into Geography. We just stumbled into taking a course that captured our interests and that we found motivating. It was about 1966, my sophomore year at Berkeley, when I took an introductory physical geography class taught by Ted Oberlander, a geomorphologist. Clearly, at that stage, it was the best course I had taken at Berkeley while I was exploring various majors. The subject matter resonated with me. A lot of what he was teaching was global ecology, but that terminology wasn’t used in those days. It was landforms, climate, vegetation, soils, and hydrology all in a single one-semester class. It was very intensive. That gave me a basis for deciding what sorts of courses to take later on. It really goes back to having a really excellent teacher. I had a lot of teachers at Berkeley who were great teachers. Berkeley doesn't necessarily have a reputation for outstanding undergraduate education, but in my experience in the Geography, Anthropology, Botany, and Forest Sciences departments, the teachers were incredibly dedicated.

What was the department like in the early 1980s when you started in the CU Geography department compared to now?

In the 1960's and 1970’s, CU was not a top-ranked research university. It was in the 1970s and 1980s when CU’s research reputation really took off. I came here during a transition period. When I was hired, there were 11 or 12 faculty. At lunch time, a small group of people would play bridge, but I didn’t have time for it. At least one faculty member would leave quite early to go play golf. About half of the faculty were not research oriented. So you can imagine that there was some tension in the department in the early 1980s because they were hiring new people who were expected to be very productive researchers. It was part of the whole policy of the university. There were senior faculty who had done some research early in their careers, but were no longer research active. Everybody had the same teaching load which was 5 classes per year. I and another recently hired faculty member campaigned to develop a differential teaching load policy which reflected the differences in the amount of research people were doing. Somewhat surprisingly, the senior faculty accepted our proposal. Within that first year, we adopted a differential teaching load which said that faculty who didn’t do research were expected to teach more courses. For the next few years, we had faculty who did teach more than the research active faculty members. Today, everybody is research active and the differential teaching load policy has not recently been implemented. But, in the early 1980s, the department was in transition from a department that historically was mostly teaching oriented to a department that was becoming a very strong research group. Now we are highly respected on and off this campus as a research oriented Geography department.

In terms of the overall atmosphere during that time, there certainly was some tension because there was an “old guard” that was close to retiring. So there were a few faculty who played key roles in the transition and I was fortunate enough to be elected to our personal committee, which in those days was treated like an executive committee in terms of advising the Chair on governance issues. I served with Dave Hill who was our department chair. During one year, he held approximately one retreat per month or about eight retreats total. It was a time of intense evaluation of our performance and setting new goals. Nel Caine and Nick Helburn were on that committee with me. So, as a brand new faculty member to be able to be elected into that committee and play some role in planning the future of the department was a wonderful learning experience for me which made me feel that much more devoted to the long-term success of the department. We’ve continued this policy of electing non-tenured, young faculty to the personnel committee. However, the personnel committee’s purview has changed over the years so that it currently deals more just with personnel issues rather than as an executive advisory type of committee.

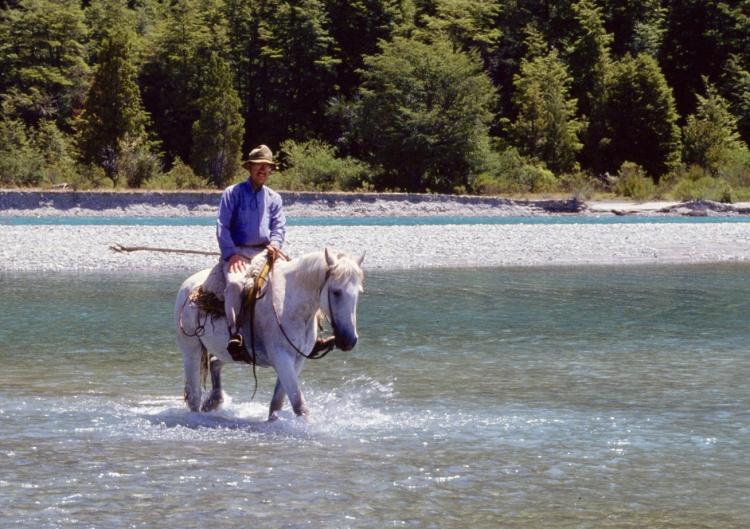

Argentina, 1984

The university did not have a formal requirement for new faculty to have mentors and I probably didn't think I needed one! I didn’t have a mentor, but I had role models — especially Dave Hill who was the chair of the Geography department. He took it as his mission to transform the department into a much more democratically governed department. Dave did not make individual decisions on his own. Six years later, I became department chair and I had his model to follow. It's sometimes easier to just make quick decisions on your own without consulting the faculty, but in the long-term, you’ve got to have transparency for faculty buy-in. We continued that trend and we’re known for being much more democratically governed than the typical department at CU. Our current faculty do a great job of participating in governance endeavors campus-wide which is important because if you don’t show up for dinner, you’re likely to be on the menu.

Now back to your question about mentors and role models. When I was just starting Berkeley, we had a visiting faculty member, a guy named Martin Kellman, very young, 27 or 28. He had just finished his PhD. He was visiting from Simon Fraser University and he was actually being considered for a job in the geography department at Berkeley. That’s how they did it in those days. He was a “Young Turk”, very critical of the status quo and very critical of a lot of the research that had been done by faculty at Berkeley in the Geography Department. But, he really kind of showed me the way. He showed me that this was a field I could get into and function in. He was an excellent teacher and role model in that regard. Not surprisingly, he did not get the job offer at Berkeley. He and I continued to communicate up until recently in fact. He’s never been a mentor in a coaching sense, but he’s been a role model because he did really high-quality, novel research. He set a standard for me to aspire to. That is the most important thing a so-called mentor can do, I believe: set standards. He did it by asking really original research questions and by developing sustained lines of research. He worked on tropical savannas in Central America. When I started to follow his research, it was obvious to me he had developed a whole line of research questions which required many, many years to address — in some cases based on long-term experiments. He was not the kind of researcher who would go for what is called today “early wins” or “low hanging fruit”. He was the kind of researcher who would articulate really important scientific questions and then devote 10 or 15 years or more to pursue those questions.

Chile, 1984

I was a young postdoc in New Zealand working with the forest service. A colleague of mine, Glenn Stewart, and I wrote a paper which was essentially a critique of the science underlying a lot of the forest management being done in New Zealand at that time. The key forest management problem was about the impacts of introduced animals. The impacts of introduced deer and opossums in terms of killing trees, changing forest structure and so on. In this review paper we presented new results, but also asked a lot of questions about the science underlying forest management. We took a draft manuscript to the most senior scientist in the forest service at that time. He was a very prestigious person. He had read over our manuscript and, of course, went out of his way to completely trash it. Then Glenn and I were about ready to get up and leave when he said, “But there’s one way I can think of to save this manuscript: if you bring me in as a co-author.” We just said, “thank you” and left. We thought our review must be a pretty good critique of the conventional wisdom if this guy wanted to be included as a co-author.

Any anecdotes involving students?

I do remember a time in early 2000s when I gave an invited keynote address at a meeting on climate change and forests in British Columbia. One of my former PhD students was there and she had been involved in inviting me to give the talk. I gave the talk involving 20-some years of research on vegetation changes in Patagonia where she had done her dissertation work. When I sat down after giving the talk, she said, “Now I understand why I did what I did”.

Tom with students. Argentina, 1991

Can you tell us a bit about how your research has evolved over the years?

It has evolved fairly radically over the years. Our entire field of biogeography and forest ecology has changed. The tools available now are just incredible. GIS did not exist when I started. When I started, we called a lot of the work that we did “landscape ecology”, but it was based on very, very tedious work involving interpretation of air photos. It could not be done in an automated way in the 1970s. I took classes in air photo interpretation from a guy who was developing some of the first remote sensing based on satellite imagery at NASA. That was in 1968 or 1969. Remote sensing was not available except to a very small group of people who were actually doing the original research at that time. That's been one of the biggest evolutions in the field of forest ecology. GIS and remote sensing technology are easily available to students now. When I got started in the late 60s and early 70s, if you wanted to use those tools, you had to go into one of those fields and become an expert. That was one of the biggest changes.

From the beginning of my career I've been very interested in how humans and natural disturbances and climate variability affect forested landscapes. That has been a common theme from the beginning to right now. I started out working in the western highlands of Guatemala for my dissertation work in 1971-72. Part of that work was ethnographically based, going around and asking the Maya-Quiche inhabitants who were working out in the forest why they're doing what they're doing and what their expectations were in the use of fire in relation to creating more favorable grazing conditions for sheep, keeping trees from regenerating in some forests, and so on. So it's kind of humorous that my first work — it was not all ethnographic but it included some ethnographic work -- was in an area which I learned later was culturally known by anthropologists as the most difficult place to do ethnographic work. The Maya-Quiche don't reveal information easily. That was certainly my experience in the field so I don't do a lot of ethnographic work anymore. Or, I collaborate with people who can devote the enormous amount of time in face-to-face communication needed for ethnographic work – while I spend more time in the forest, coring trees and sampling the vegetation.

Argentina, 1993

Was there ever a moment where an epiphany “hit you in the face” in your research?

I’ve had a couple of experiences where, in the field, it hits you in the face so hard that it's clear. In 1975, I started working in Chile and teaching at the forestry school there for 4 years. I arrived in the winter and everything was under snow. The roads were washed out. I had been studying forest inventories which were performed for timber extraction. The forest inventory showed that the population and size structure of the forest had a dearth of small, young individuals of the southern beeches (Nothofagus) species, which is the most import genus of temperate tree species of the Southern hemisphere. So there’s this puzzle: how do we have these forests that are dominated by old trees, large trees of these particular species, but you don’t find any small, young ones. You don’t find any intermediate sized trees. The vast majority of the trees of this species were about a meter in diameter or larger and hardly any smaller than that. So that was the puzzle. I went out to the field once roads dried out a little bit, and looked around the landscape. The landscape was full of landslides and mass movements caused by the 1960 mega quake that affected the Valdivia area in southern Chile — that’s a city where I lived. At the time, that was the strongest historical earthquake. That earthquake produced thousands of landslides all over the Andes. That's where these trees were regenerating—on landslide scars, on landslide deposits, and on the flood deposits associated with damming by landslide debris and subsequent breaching. It was that simple and that obvious.

Argentina, 2001

So, were you the first person to discover this?

For the Southern Hemisphere, yes. There were a group of maybe seven or eight researchers in the 1970s who were really pushing that new paradigm based on research that was done in the northeastern US and in the Pacific Northwest. There were always a small number of people who challenged equilibrium thinking going back to the 1930s and 1940s, but they did not “carry the day” in terms of what was accepted theory at the time. In the 1960s, equilibrium theory was taught in biogeography and ecology textbooks. Today, non-equilibrium theory is the dominant mode which explains why so many forest ecologists spend so much time quantifying the spatial and temporal patterns of disturbances such as fire, insect outbreaks, windstorms, etc.

Tom with students. Colorado, 2005

That's been a source of incredible satisfaction for me. They make the point that the work we were doing in the mid-1970s was actually ahead of a lot of the work that was being done in the Pacific Northwest and the northeastern USA. That was their judgment and I would tend to agree with that statement actually.

Was this the awareness that you said “hit you in the face”?

Yes, exactly. I understood the theoretical literature. I had done my homework so I knew that the dominant paradigm of equilibrium thinking was a weak paradigm to begin with. I went to the field -- it was not GIS, remote sensing, etc. No: it was natural history - just going around and identifying what's in the understory of the forest, what’s not regenerating and going climbing, literally climbing on these landslides, to document that the shade-intolerant species were abundantly regenerating on those exposed sites with lots of availability of light. The work that we did at that time was contrary to a lot of the general successional theory that was in the textbooks. But, we were not alone. There were many other people who were showing how that theory just did not apply.

You started to mention something else earlier. Was there another epiphany?

The other epiphany is when I first came to Colorado in the early 1980s. My goal was to quantify what we called “disturbance regimes” such as the spatial and temporal patterns of disturbances like fire, bark beetle outbreaks, spruce beetle, mountain pine beetle, wind storms, etc., generally across all the forest types in Colorado. We've done that. I can remember one of my graduate students laughing and saying: you are never going to get this done. Well, we actually have done an awful lot of it.

Tom and Juan Paritsis. Argentina, 2007

Regarding your research, what are your fears and concerns for our collective future?

My major concern is that special interests will fail to use the existing science where there is an existing consensus about most of the work that we do. There are debates about particular things, but for the most part, everyone who is a serious scientist in forest ecology is in agreement that warming temperatures are accelerating all those big disturbances and tree mortality events.

That's my big concern and it's really important that researchers -- not just academic researchers like myself who are in a very privileged position because we have tenure and we don't really have to worry about political repercussions -- but for the researchers who work for land management agencies. They are in a much more difficult situation. So my concern is that we do not allow the politicians and the special interests to bully people into being silent. That's easy for me to say as a tenured faculty member at CU which, I think, has performed pretty well insulating faculty from political pressures. But, if I were working for a federal land management agency, it would be much more difficult. And I've been there, in New Zealand, so I've gone through an episode where there was a lot of opposition to our work. In the case of New Zealand what I saw, which was really great, is that if you had good leadership at the top, then the scientists were encouraged to just objectively present their scientific results. So, it really depends on the quality of the leadership at the top.

In our system, it would be the Chief of the Park Service, Chief of the Forest Service, and so on. Those career government employees standing up against the political pressure are at risk. So that's my real fear: that it's a challenge for people working on climate impacts on forests to continue doing their public outreach without fear of some retribution or some sort of frustration for their career development. Of course, I saw that in Chile because I was working there during the Pinochet dictatorship. It's not just the issue of people who disappeared during those time periods, but it's also the issue of people who were no longer welcome in certain environments, like in their equivalent of the Forest Service, because they were suspected of being on the other side politically. So, yes, I'm worried about political influence on the conduct of science. It's a pretty threatening situation right now.

The impact of special interests is world-wide, but it should not be as extreme as it is in the U.S. given our level of education. We are probably the worst, but Australia has had some pretty serious problems in recent years trying to quiet climate change scientists and downsizing climate change research organizations. So it's not entirely just the U.S. but, among developed countries, we should be extremely embarrassed about this.

Tom coring a tree. Colorado, 2013

Regarding your research, what makes you hopeful for the future?

What makes me hopeful is the fact that the quality of the people who decide to devote their professional lives to research on biogeography and forest ecology is fantastic. Young people are picking up skills very quickly and they're really motivated. They’re excited. They’re passionate about their work. I’m very excited about the quality of research in the environmental sciences. I’ve taught our research design class for many years which means, at the graduate level, that class keeps me up-to-date on work that’s being done in geomorphology, climate science, remote sensing applications, snow hydrology, and so on. I've seen tremendous progress there and you just can't keep that information from eventually having an impact.

Climate change is not going away. That means, over time, the scientific evidence in support of understanding the causes and impacts of climate change is going to be increasingly overwhelming and compelling. We're going to win this battle in the long-term.

In a lot of our land management agencies, they view an administration as being in power for probably 4 years, and at the most, 8 years. The people working there don't radically change their fundamental beliefs. They may have to mute themselves for awhile but, in the long-term, they know resource management and adaptation issues are not going to go away so there’s going to be a need for their knowledge and their activities in the future.

Have you seen a change in the quality of students at CU?

In the early 1980s CU had even more of a reputation for being a party school at the undergraduate level. There's been an improvement in the quality of the undergraduates, which is reflected in a more serious attitude. I think this is backed up by the test scores and the class rankings of the students at the high school level who are admitted. Yet, I know there recently have been numerous instances of disrespectful behavior towards faculty and teaching assistants which is very concerning. At the graduate level, there’s really no comparison. In the early 1980s, the qualifications of the applicants to our graduate program were much less than the qualifications of the students over the last 20-25 years. That just reflects the fact that the faculty has changed so much and, if you have outstanding researchers as faculty, they attract outstanding graduate students.

What advice can you give to students about their careers and the study of Geography?

At the graduate level, for people who are considering an academic or research-oriented career, the key thing is to find out what you're passionate about and what you want to do on a regular basis. Do you want to stare at a computer all day? Do you want to stare at a computer part of the time and have a lot of time out in the field digging snow pits, soil pits, coring trees or whatever it is? You have to think in practical terms of how you would like to spend your time. Do you want to be indoors, outdoors? And then, intellectually discover what you’re passionate about. It’s a little trite to say it, but you want to learn what you love to do and then figure out how you can do what you love. University faculty are very privileged in terms of setting our own career goals and, to a large extent, how we spend our time. In my case, the vast majority of my time is spent on things I enjoy, doing what I love. There are always some things you may not really like, but for the most part, faculty can determine what they do. It’s as simple as “love what you do” and “do what you love.” That’s not true in any other field I’m aware of. It’s certainly not true for my colleagues who have worked for land management agencies where it’s a very top-down structure. You are typically forced into administrative positions after doing 10 or 15 years of mostly doing research. That can be very satisfying for some people, but others just want to keep doing research.

What is your hope for graduate students coming through the CU Geography program?

My hope is that they keep on doing what our past students have been doing. Our department ranks very near the top in terms of placement of our PhD students into PhD granting departments. I haven't looked at the data for a while, but we're either 1st or 2nd and Berkeley is either 1st or 2nd. That's remarkable because CU as an institution is not one of the top 2 or 3 universities overall, although we're doing very well. But, our department is able to place our graduate students in the top academic departments around the world. And so, that's my hope, that we can continue to attract the kind of students who are motivated to pursue academic careers and get the most rewarding, demanding jobs in other PhD granting departments. That is admittedly a very elitist view and that’s fine with me. Someone has to be at the top and I think it is our graduates who should be there. That’s what we should continue to aim for. At the same time, we all as faculty, look at the markets and ask, “What are the employment possibilities going to be in the future?” So, we have to stay on top of that, but I think our past success in placing graduate students in top institutions is something we should continue to build on.

Of what are you most proud?

Of what are you most proud?

Clearly it's the accomplishments of my students. I've had 33 PhD students graduate from CU and I've got another 4 PhD students in the works right now. I'm extremely proud of how those students have gone on to have a lot of accomplishments as researchers and teachers and to educate their own graduate students, who have gone on to train and educate other graduate students. If you look at the career of many researchers, you’ll see a common pattern where, in the early years, the young researcher is doing it all with a few research assistants on a temporary basis. Then, over time, we tend to adopt a more managerial role where we hopefully can duplicate or triplicate the kinds of impacts we would have if we were still to continue to do just everything on our own. So, I feel very satisfied that I have former students, especially in Chile and Argentina, who are the top people not only in their countries in their respective fields, but they're among the top people in the world in their respective fields. And, based on the continued interaction I have with them and their students, they are people of good values and good professional values. I'm currently co-supervising a PhD student in Argentina who is my academic great granddaughter. That's really, really satisfying. While I’m co-supervising, her main supervisor did his PhD with one of my former PhD students here so he’s my academic grandson. That’s cool. You can see the carryover and evolution of the ideas we were working on in the 1980s. They changed quite a bit and we have found new questions related to those ideas, but now another generation is working on it. The fact that I have former students teaching and leading research groups in Chile and Argentina is probably the thing I’m most proud of.