Xiaoling Chen, PhD Candidate, Geography Department, University of Colorado Boulder

“For the People’s Health”: Transforming Hospital Spaces, Recasting Medical Expertise

Ling is a coastal, hilly county in Southern China with a humid and semi-tropical climate. Although having a population of over one million, it is at times considered rural, with pockets of farmland and individual houses within its urban areas and sprawling farm villages drastically giving way to urban concrete high-rises. I came to study the healthcare landscape of China as shaped by the post-2009 governmental health care reforms, focusing on the everyday experiences of healthcare workers and patients. Although invisible among the physical structures, the healthcare landscape was just as solid in the lives of people. Since 2020 though, it has become increasingly noticeable due to Covid-19 as blockades and checkpoints appear in public spaces, communities, business areas, and local markets. Throat swabs, health apps, and masks have become necessities for healthcare workers and ordinary people on a daily basis.

I began fieldwork from July 2021 and started participant-observation and interviewing at Ling’s People’s Hospital as a visiting scholar. Occasionally, I visited the Hospital’s collaborative institutions in townships, as well as COVID-19 vaccination and saliva sampling sites. In China, county and city seats are considered urban areas, and townships and villages rural places. The Neurology Department and its affiliated Stroke Center for Comprehensive Prevention and Treatment which hosted me, treat elderly with cerebrovascular diseases – China’s number 3 killer. The Stroke Center also provided me a unique opportunity to observe how a system under transformation responds to the nationwide impacts of an aging society.

After 50 years of reform and opening up, the images people have of China include gleaming cities and fast trains crisscrossing the country. Just as dramatic, yet unnoticed, have been the changes to the institutions and ways of providing healthcare. The evolution from a socialist top-down approach of providing public services, the influence of modern healthcare ideas from outside, and changing norms of what healthcare is, have intersected to transform hospital spaces and created new ways for “doing” healthcare, under the auspice of a political system with changing values, processes, and means.

Political turmoil between 1950s and 1970s witnessed the difficult birth of an expansive, socialist public health network that provided cheap, basic care to all its citizens in an egalitarian manner. This network was composed of many small rural clinics and relatively few urban hospitals. To some, this period might be considered the era of public health as the changes helped improve the general health of China’s population through preventative measures. However, healthcare in curative terms remained minimal.

Political turmoil between 1950s and 1970s witnessed the difficult birth of an expansive, socialist public health network that provided cheap, basic care to all its citizens in an egalitarian manner. This network was composed of many small rural clinics and relatively few urban hospitals. To some, this period might be considered the era of public health as the changes helped improve the general health of China’s population through preventative measures. However, healthcare in curative terms remained minimal.

The Reform and Opening Up era (1980s-2000s) saw the emergence of a fragmented “neoliberal” health system. The system lacked public funding and profited from selling drugs (with up to a 15% markup) and curative care. During this period, thanks to many historical and contemporary factors such as administrative endorsement, expertise, and reputation, public hospitals in cities and counties outgrew primary health care institutions as well as private entities. Primary health care institutions were those small-scale facilities located in townships, urban communities, and rural villages.

The socialist public health network was dismantled, and healthcare demand increased. It was estimated at that time that large-scale urban public hospitals would attract up to 90% of patients, creating a nationwide problem of low healthcare accessibility and affordability. During this period, public healthcare facilities were only public in name and operated with a profit motive. Social discontent arose and medical disputes pervaded hospital spaces, while healthcare professionals suffered, or even died from assaults by patients and their family. These issues have lingered until the present.

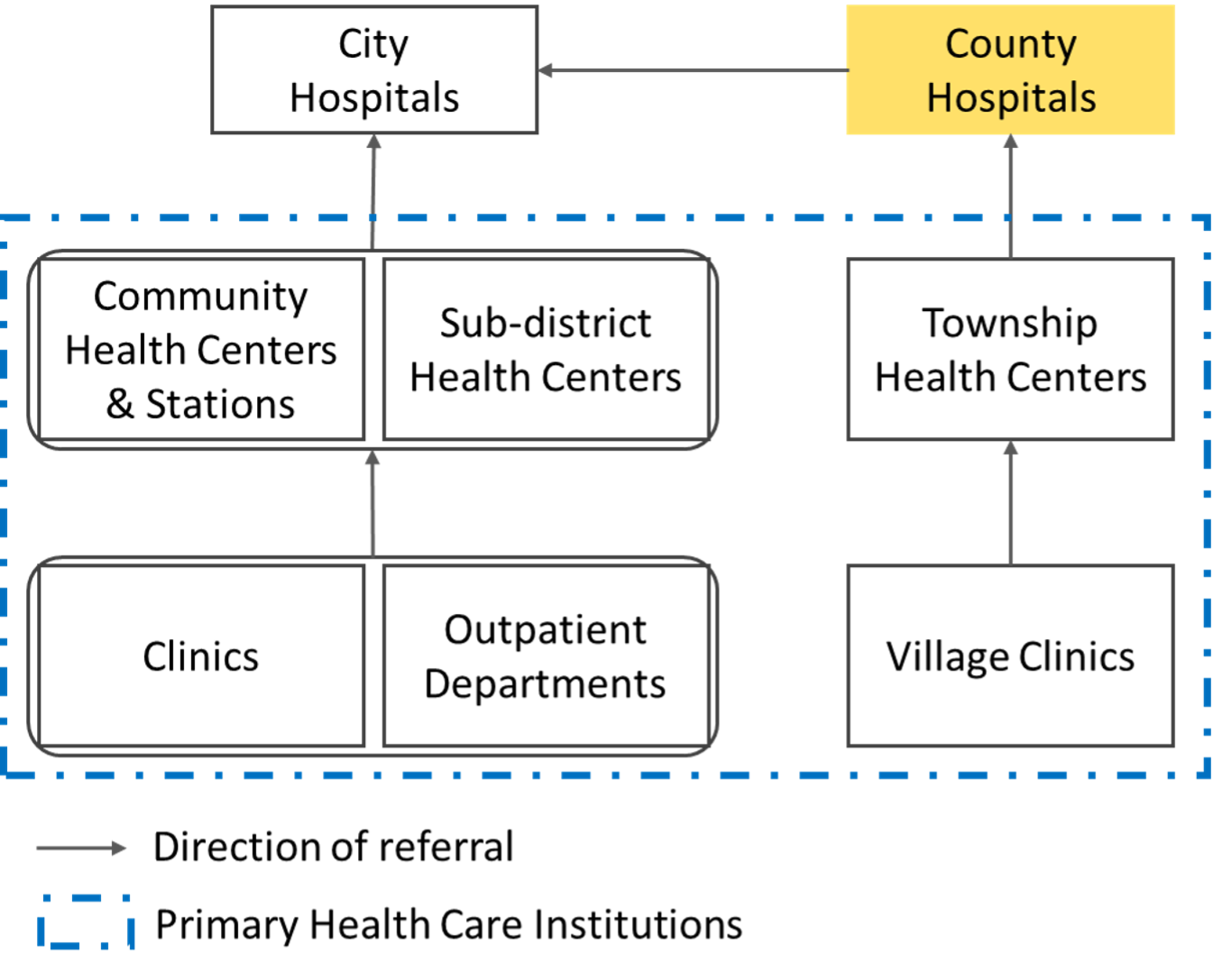

In 2009, the central government, through a new round of health care reform, attempted to strengthen administrative control over all public healthcare facilities. It hoped to (re-)establish a hierarchical health care system (Figure 1) which upholds its socialist, public nature to provide affordable healthcare and to meet the population’s increased yet unsatisfied health demands.

Figure 1. China’s Hierarchical Health Care System

While history and the government goals seem straight-forward, reality is messy and unpredictable. A public hospital is more than a physical space that passively absorb any reform impacts. Social actors – hospital administrators, doctors, nurses, patients and their caregivers - create and recreate the place’s structures, operational mechanisms, and relationships, on which parts of their aspirations and identities reside. This workspace is infused with sociocultural norms and local interpersonal relationships (i.e. renqing and guanxi). Boundaries between work and home, and between healthcare as a common resource and a private good, get blurred. Reform policies seep through the everydayness of such a space, negotiating with and reconfiguring these structures, relationships, and mechanisms.

The logics of spatial inequalities in public funding, healthcare expertise, and income levels along the line of administrative division run deep in the health care system. Primary health care institutions are now entirely publicly funded and expected to serve a large proportion of patients as their expertise improves; many have expensive, state-of-the-art medical devices they could not afford prior to 2009.

Despite these orchestrated efforts, many primary institutions lack proper manpower due to low wages and dire career prospects, leading to poor health-care provision capacity. What’s worse, paid on flat monthly rates of less than 1,000 USD, as determined by local economies, doctors in primary institutions are unmotivated to admit patients. Instead, they are inclined to refer patients to urban public hospitals, avoiding work and possible medical disputes altogether; some also run private clinics during work hours to earn an extra paycheck. Idle machines and employees, and empty beds, patient wards, and waiting areas are not uncommon.

Despite these orchestrated efforts, many primary institutions lack proper manpower due to low wages and dire career prospects, leading to poor health-care provision capacity. What’s worse, paid on flat monthly rates of less than 1,000 USD, as determined by local economies, doctors in primary institutions are unmotivated to admit patients. Instead, they are inclined to refer patients to urban public hospitals, avoiding work and possible medical disputes altogether; some also run private clinics during work hours to earn an extra paycheck. Idle machines and employees, and empty beds, patient wards, and waiting areas are not uncommon.

Public hospitals, contrary to the primary institutions, remain underfunded and incentivized to make profits. Meanwhile, they are subject to increasingly stringent policies from a growing list of regulators including the National Healthcare Security Administration and the National Health Commission through their local agents. In particular, public county hospitals, sandwiched between city hospitals and primary institutions, are still over-crowded with patients, some with ailments as minor as a cold.

Many doctors think their hard-earned expertise is not being adequately used, and their hard-work (as well as overwork and holiday-stripped shifts) insufficiently rewarded and respected. Thus, it has become increasingly difficult for doctors and nurses, physically and emotionally depleted, to empathize with their patients, creating a breeding ground for mistrust and disputes. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the large group of medical professionals in public county hospitals form a buffer zone for public discontent over the flawed health care system.

China has reportedly achieved its goals of universal healthcare from the perspectives of patients. Such successes include sustained health insurance coverage rates of over 95% since 2011, and affordable healthcare to a large population in need – with merely 30% out-of-pocket health expenditure. However, how the process changes hospital spaces remains poorly studied. My research provides a unique account of everyday experience in hospital spaces, by working closely with actors like doctors, nurses, patients, and caregivers to form a comprehensive picture of healthcare provision in the new reform era.

This field trip is made possible by the generous support from the Geography Department through the Jennifer Dinaburg Memorial Research Award and the Solstice Graduate Research Award, from the University of Colorado Boulder through the Beverly Sears Graduate Student Grant award and the Center to Advance Research and Teaching in the Social Sciences (CARTSS), and from the Society of Woman Geographers through the Evelyn L. Pruitt National Fellowship for Dissertation Research. I will return onto campus by fall 2022 and begin my dissertation writing process.